"Work to be Done": Attacking School Reform

Before the women of the WABPS could tackle school reform, they needed to fully understand what they were up against. The primary way that they approached this was by sending members of the organization (Field Workers) out into the state to survey rural schoolhouses. Field Workers primarily travelled by horse and buggy or by train and took note of schoolhouses that needed improvement or, in the most extreme cases, needed to be replaced.

This was not the first time that surveys were conducted in the state. In 1889, Charles McIver and Edwin Alderman were sent out by the state legislature to hold institutes for teachers and speak to people about education. Their trips were far less extensive than the trips of the WABPS, but people seemed more willing to listen than when the women were making their rounds fourteen years later.

WABPS field workers often began their journey by finding the superintendent of the county they were visiting. They would gather information on the local schools and any teacher’ organizations in the area, and get a general understanding of how locals felt about reform efforts. In 1902, when Field Worker Leah Jones found a distinct lack of interest in education in Craven County, she interrupted picnics, church meetings, and any other gathering places to discuss the need for reform. During that same trip, Jones sent pamphlets out to every township in Craven County, the school committeemen for each township, the county Board of Education, and the teachers of the county. She also sent letters to each member of the county Education Committee asking to be notified of any gatherings in his area and if he could call “a meeting of the ladies to discuss the school-house question.” Out of the thirty letters she sent to committeemen and superintendents, she received six replies.

In order to accomplish their goals, the women of the WABPS had to formulate a plan to interest the public. First, they had to demonstrate to local parents the conditions of the public schoolhouses in which their children spent much of their time. Second, they had to make the school the center of social life in local communities. Third, they had to make the schoolhouse the model of “cleanliness and beauty” for each home that it represents. Finally, they had to cultivate a culture in which everyone cared for the children of the state as if they were their own.

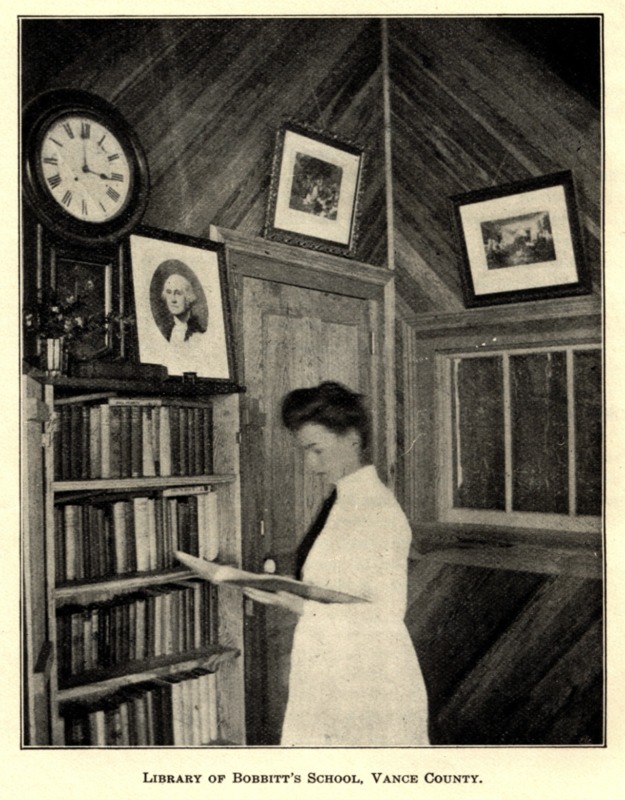

The WABPS were ultimately attacking education reform on two fronts: health and beautification. Beautification included cleaning up the school grounds, furnishing the classrooms, purchasing books and patriotic materials for students, and setting standards for how schoolhouses should look and what should be provided. Their health goals included installing latrines and improving sanitary conditions, digging wells so children could have better access to fresh water, and ensuring that students were clean and well-groomed for school each day. They decided to focus on these two goals as a way to reform schools from the bottom up. If they could improve the schoolhouses, the wellbeing of the students, the attitude of the parents, and the tools of the teachers, they could make a stronger case for increased funding for education across the state and the construction of new libraries for students.

During the initial survey trips, rural schoolhouses were found to be in various states of disarray. Viola Boddie, another Field Worker, reported that some schools she visited were simply one-room log cabins with gaps in the logs wide enough to “throw a cat through, if not a dog.” Jones reported that many schools had little more than a ceiling, a few windows, a stove, rough benches, and a four-foot by three-foot blackboard. The only recreation areas that these schools had were "the road." The primary concern regarding health was that many rural schoolhouses had no indoor plumbing and no convenient water source; “a clean body goes a long way towards making a clean soul.”

So why did they choose to focus on health and beautification? What may seem superficial became a very significant and methodical aspect of the WABPS plan. Their ideal school lot would include natural features like trees, shrubs, brooks, or streams. If the area didn’t have these features, the WABPS encouraged teachers and students to plant flowers, trees, and other greenery. They wanted all schools to have easy access to water (usually a well) and a playground for the schoolchildren. Later, in 1908, Mrs. McIver corresponded with Warren Manning, one of the country’s leading landscape designers from Boston, Massachusetts. She requested that Manning prepare a memorandum for her to distribute to schools across the state with the ideal design and layout for schools grounds. You can read his suggestions below.

In addition to improving the physical landscape of the school grounds, the WABPS also made a conscious effort to add patriotic materials to the classroom and various forms of entertainment for the students. By creating a comprehensive guideline for the improvement of public schoolhouses across the state, the WABPS could create safe and clean places for students to learn and foster a sense of unity among teachers, parents, and children.

By 1904, educators across the state had caught the spirit of the WABPS, even in areas where the women were not organized. According to Boddie, this momentum was exhibited across North Carolina by increased attendance, cleaner schoolhouses and grounds, the increased desire for books and pictures, and state-wide efforts to secure longer school terms and more efficient teachers.