Scarlet Trimming

By Effie Lee Newsome

Annotations by Karen Kilcup

The woodpecker folk are quite fond of bright red— Poinsettia scarlet for neck or for head.[1] And whether the costume is brown, black or gray, They count on red hats or red scarfs to make gay. The dignified flicker, with linings of gold,[2] The black and gray downy that weathers the cold,[3] The jaunty old red-head in jockey outfit—[4] All choose blurs of scarlet to cheer up a bit.

Newsome, Effie Lee. “Scarlet Trimming.” Gladiola Garden: Poems of Outdoors and Indoors for Second Grade Readers. Washington, DC: Associated Publishers, 1940, 77.

[1] Poinsettia are flowers native to Mexico that for many symbolize the Christmas holiday. Ordinarily red, they now come in many colors.

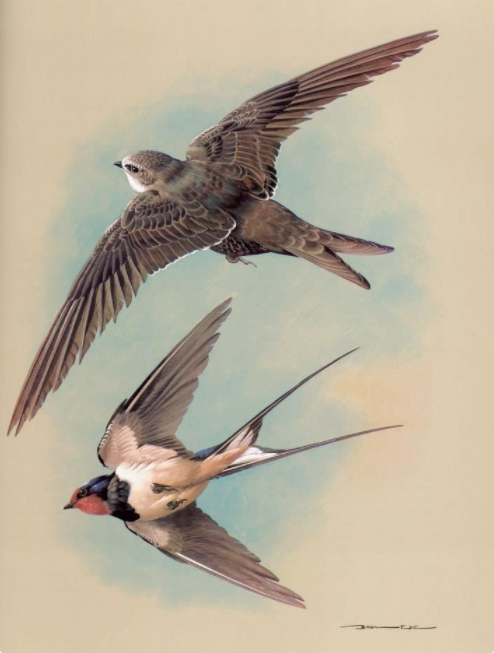

[2] The Northern Flicker is a large brown and gray woodpecker with a spotted breast and red hat. Coloration varies across the United States, where they are year-round residents.

[3] The Downy Woodpecker is a small bird that lives year-round in most of the United States. Only males have the characteristic red cap.

[4] Both female and male Red-Headed Woodpeckers have an entirely red head. Their bodies are white, and their wings are bright white and deep black. Now in decline in the U.S., they defend their home territory fiercely.

Contexts

Newsome worked among the many celebrated writers of the Harlem Renaissance, who included Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, James Weldon Johnson, Zora Neale Hurston, and Anne Spencer, many of them poets. Among her noteworthy contributions to that movement was her writing and editing for W. E. B. Du Bois’s magazine, The Crisis, the official publication of the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People). As John Claborn points out, Du Bois’s political goals embraced the idea of access to natural spaces, and the magazine featured environmental writing by such notable authors as Arna Bontemps, Claude McKay, and Hughes. Newsome contributed to and edited “The Little Page” (“Whimsies for the Younger Folk”), where much of her work emphasized nature. This poem, like many others in The Envious Lobster, whimsically enacts a natural history lesson, while it encourages children’s imagination.

Resources for Further Study

- Claborn, John. “The Crisis, the Politics of Nature, and the Harlem Renaissance: Effie Lee Newsome’s Eco-poetics.” Civil Rights and the Environment in African-American Literature, 1895-1941. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

- “Effie Lee Newsome, 1885-1978.” Poets.org. This site provides access to seven of Newsome’s poems.

- Newsome, Effie Lee. Gladiola Garden: Poems of Outdoors and Indoors for Second Grade Readers. Courtesy of the New York Public Library, this site provides access to the entire text.

Contemporary Connections

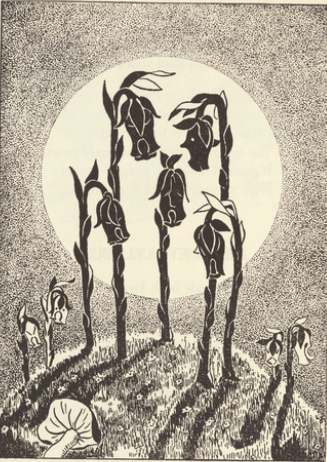

Anonymous. Reading of Newsome’s poem, “The Bronze Legacy.” The illustrations for Gladiola Garden were done by prominent Black artist Loïs Mailou Jones (1905-1998).

Johnston, Amber O’Neal. “African American Poetry: Effie Lee Newsome. Heritage Mom blog.