Song for a Banjo Dance

By Langston Hughes

Annotations by Rene Marzuk

Shake your brown feet, honey,

Shake your brown feet, chil',

Shake your brown feet, honey,

Shake 'em swift and wil'—

Get way back, honey,

Do that low-down step.

Get on over, darling,

Now! Step out

With your left.

Shake your brown feet, honey,

Shake 'em, honey chil'.

Sun's going down this evening—

Might never rise no mo'.

The sun's going down this very night—

Might never rise no mo'—

So dance with swift feet, honey,

(The banjo's sobbing low),[1]

Dance with swift feet, honey—

Might never dance no mo'.

Shake your brown feet, Liza,

Shake 'em, Liza, chil',

Shake your brown feet, Liza,

(The music's soft and wil').

Shake your brown feet, Liza,

(The banjo's sobbing low),

The suns's going down this very night—

Might never rise no mo'.

Hughes, langston. “song for a banjo dance.” THE CRISIS 24, NO. 6 (OCTOBER 1922): 267.

[1] Although today the banjo is mostly associated with bluegrass music, the earliest iterations of this musical instrument “were played exclusively by the enslaved at least two hundred years before whites ever considered laying hands on what was, to the slaveholding culture, a ‘primitive’ instrument.”

Contexts

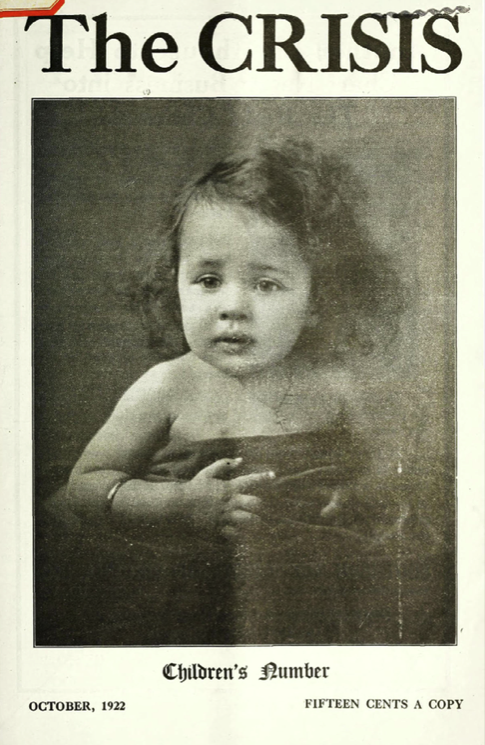

Starting in 1912, the October issues of The Crisis, the official magazine of the NAACP, were dedicated to children. A typical edition of these children’s numbers would contain a special editorial piece and two or three literary works specifically for children, while still including the serious pieces about contemporary issues with a focus on race that The Crisis was known for. These October numbers were sprinkled with children’s photographs sent in by the readers.

In his first editorial for the Children’s number in 1912, W. E. B. Du Bois wrote that “there is a sense in which all numbers and all words of a magazine of ideas myst point to the child—to that vast immortality and wide sweep and infinite possibility which the child represents.”

The success of The Crisis’ children’s number led to the standalone The Brownies’ Book, a monthly magazine for African American children that circulated from January 1920 to December 1921 under the editorship of Du Bois, Augustus Granville Dill, and Jessie Fauset.

Resources for Further Study

- A photo essay by banjo scholar and performer Tony Thomas traces historical relationship between the banjo and African American musical culture.

- The Creole bania, the oldest existing banjo, came from Suriname, in the Caribbean, and is on permanent display at the Tropenmuseum in the Netherlands.

- Dena J. Epstein’s 1977 Sinful Tunes and Spirituals traces the history of African American music up to the Civil War. The book was the culmination of Epstein’s twenty-year research. She touches upon drums, banjo, and other instruments.

Contemporary Connections

Paul Ruta. “Black Musicians’ Quest to Return the Banjo to Its African Roots.”

In 2014, Malian n’goni player Cheick Hamala performed together with bluegrass banjoist Sammy Shelor and multi-instrumentalist Danny Knicely at the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center in Charlottesville, Virginia. The n’goni is the traditional string instrument that evolved into the Banjo in North America. The concert was aptly named “From Africa to Appalachia.”