The Mocking Bird

By Alexander Posey (Muskogee Creek)

Annotations by Karen Kilcup

The Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands.

Courtesy Wilson Library, UNC Chapel Hill.

Whether spread in flight, Or perched upon the swinging bough, Whether day or night, He sings as he is singing now— Till ev’ry leaf upon the tree Seems dripping with his melody![1]

Posey, Alexander. “The Mocking Bird.” Indian School Journal 6, no. 10 (April 1910): 30.

[1] The Northern Mockingbird inhabits most of United States and Mexico year-round. Known for its personality, the bird is famous for its singing ability, which enables it to mimic many other birds. They defend their nests boldly.

Contexts

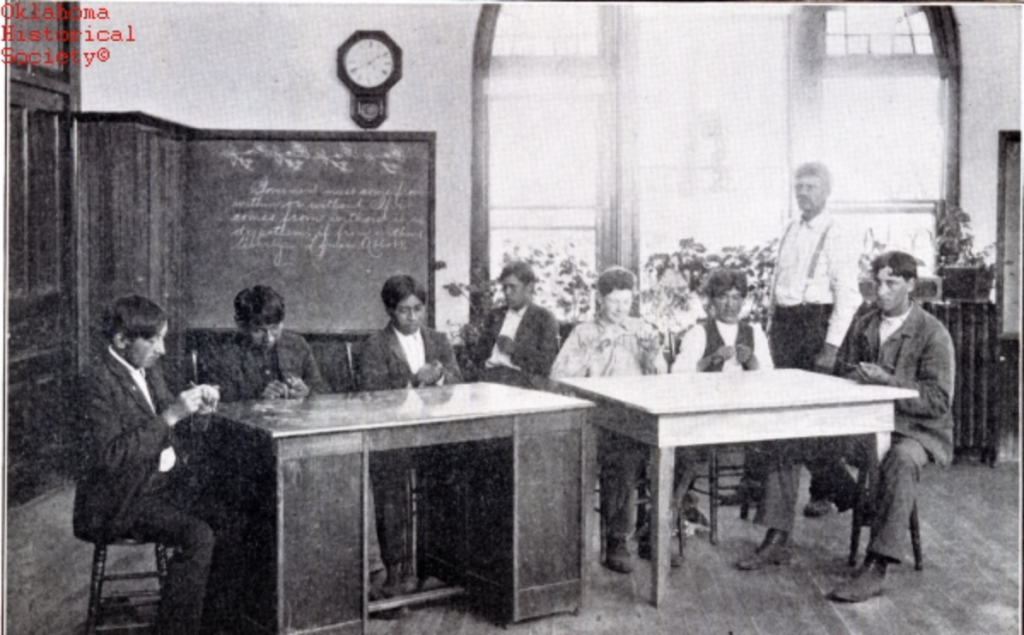

The Indian School Journal was the official publication for the Chilocco Indian Agricultural School (also known as the Haworth Institute, the Chilocco Indian Agricultural School, and the Chilocco Indian School). Located in north-central Oklahoma near the Kansas border, it began taking students in 1884, enrolling 150 from seventeen tribes that first year. Enrollment had more than doubled by 1895, with students coming from various tribes, including the Cherokee, Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Pawnee tribes. The Oklahoma Historical Society notes that “significant enrollment from the so-called ‘Five Civilized Tribes’ did not occur until after 1910 but by 1925, Cherokee constituted the largest single tribal affiliation at the school (26 percent of approximately nine hundred students).” Following World War II and the expansion of public education, the school enrolled mostly students who lacked access to such education.

Like most federally funded Indian schools, Chilocco sought to assimilate Native children into white society. Also like other schools, it stressed “industrial” education—manual and domestic labor—over academic pursuits, aiming to train them as workers for white families. Education at Chilocco was notably militaristic; students attended weekly Christian religious services, also intended to weaken their ties to family and tribe. In the 1950s, student numbers peaked at around 1300, and the school closed in 1980. Muskogee Creek poet, journalist, and humorist Alexander Posey was a nationally known writer whose appearance in the school’s magazine suggests his powerful influence on young Native American readers. Following his tragic death by drowning in the Oktahutchee River when he was only 34 years old—and only a few months after The Indian School Journal published several poems—his wife Minnie collected his work in The Poems of Alexander Lawrence Posey. His evocative poetry is also available through the Academy of American Poets (poets.org) and The Adrian Brinkerhoff Poetry Foundation. The Envious Lobster uses the versions Posey published in the school’s magazine.

Resources for Further Study

- Archuleta, Margaret L., Brenda J. Child, and K. Tsianina Lomawaima (Mvskoke/Creek Nation of Eastern Oklahoma, not enrolled), eds. Away from Home: American Indian Boarding School Experiences, 1879-2000.

- Connelley, William Elsey. “Memoir or Alexander Lawrence Posey.” In The Poems of Alexander Lawrence Posey. Ed. Mrs. Minnie H. Posey. Topeka, KS: Crane and Company, 1910. Pp. 5-65.

- Higgs, Richard. “The Oktahutchee Claims One of Its Own.” This Land, April 10, 2013.

- Littlefield, Daniel F. Jr. Alexander Posey: Creek Poet, Journalist, and Humorist. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992.

- Lomawaima, K. Tsianina (Mvskoke/Creek Nation of Eastern Oklahoma, not enrolled). “Chilocco Indian Agricultural School.” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Oklahoma Historical Society.

- Lomawaima, K. Tsianina. (Mvskoke/Creek Nation of Eastern Oklahoma, not enrolled). They Called It Prairie Light: The Story of Chilocco Indian School (1995).

- Wilson, Linda D. “Posey, Alexander Lawrence (1873-1908).” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.

Contemporary Connections

“At Length with K. Tsianina Lomawaima.” At Length with Steve Scher. February 10, 2016.

“Chilocco Through the Years.” Firethief Productions. Chilocco History Project, August 2, 2019.

Douglas, Crystal. “A Look at the Chilocco Indian School.” The Kaw Nation: People of the Southwind. Fife, Ari. “At one former Native American School in Oklahoma, honoring the dead now falls to alumni.” The Frontier, July 21, 2021.